I have been working to bring full closure to my time with Benedictine College. This is an unbelievably large event in my life. I reflected on some neutrals and positives in the first Closure post. Then I wrote a lengthy record of some negatives—things that I wanted to put behind me, having learned from them. I have password-protected that post; the public version is here.

Onward now through some reflections on music, musicians, and conducting.

Before every semester with every major ensemble, processes occur. In the ideal:

- repertoire is chosen months in advance

- essential score study proceeds, in depth, before the term begins

- all the individual parts are in hand and ready to distribute no later at (or before) the first rehearsal.

However, life is not ideal, and sometimes, there is a hitch. Because performing new music alongside time-tested music is desirable, and no library is complete, the process always includes purchases of new, which in turn involves other staff members. There can be delays, and the rental rigamarole can be daunting. Once the music is in hand, some preparation of parts is sometimes necessary. In the case of orchestral music, a good amount of desirable, older repertoire is available free of charge through online sources (primarily imslp.org). When those parts are printed, pagination and collation must be considered and attended to. Parts should be assembled so that no player must stop playing in order to turn a page; this goal is not as easy as it might seem. I must have done this for 200 pieces, and grad students assisted with some of that during my time at another institution.

On one hand, it’s a labor-intensive, blinding task (protect your eyes when using a copier!).

On the other hand, every single part copied of every musical work represents anticipation of music-making, and that makes it all worthwhile.

Part prep and assemblage were 95+% the work of my own hands, and I completed it with the knowledge that all the paper parts represented good things to come. I sometimes looked at the task as time-consuming, and I would have preferred to study the scores and practice certain gestures. But the preparation of parts for the musicians is such an essential element of ensemble musicking, and I will miss figuring out just how best to paginate the violin or flute or horn parts, taking care to fold the 11×17 paper, or to tape the pages together just right. I sometimes received assistance from my son, and I most recently benefited from the bowing work of our concertmaster.

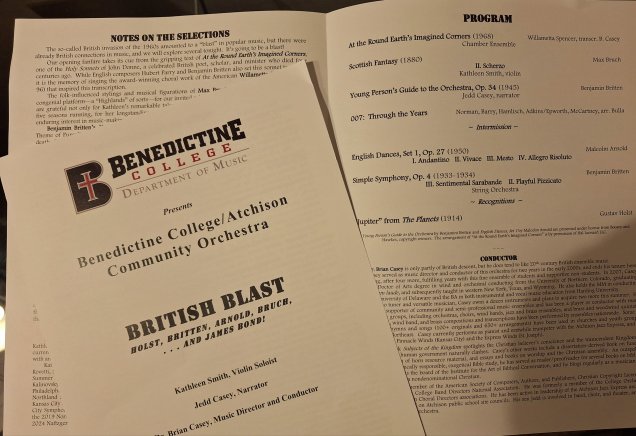

As stated in the first closure post, I believe I programmed a tremendous concert of great music for April 2024. This one was special and needed extra power. The program was “British Blast,” and there was a lot of large-scale, British music.

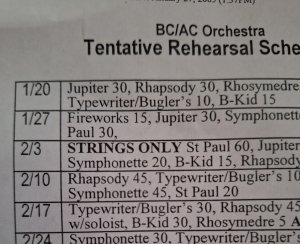

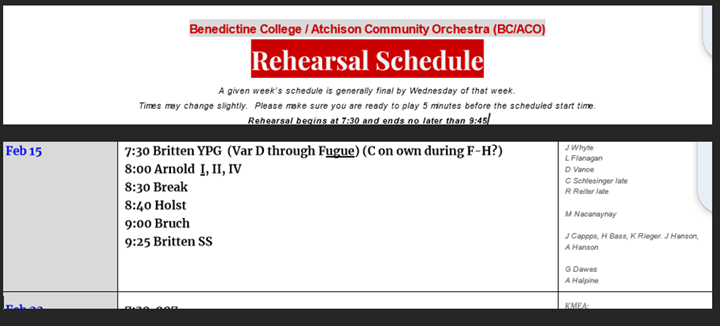

Late addition: In my head and heart, a sense of coming “full circle” was present. The top of the rehearsal schedule from 19 years ago is reproduced below, and below that, a sample from spring 2024. I had neglected to take the link out of my browser’s shortcut toolbar, but I’ll do that now, with sadness.

Background and Back-Room Planning

Enjoying variety as I do, I have typically programmed for at least one variant group in each large-ensemble program. A duo in the lobby before the performance proper; a string quartet post intermission; a brass ensemble to open a program; a chamber wind or chamber orchestral group to vary the textures at another point in the program. In other words, a concert is never completely filled with pieces that use all the instruments available. Here, I’m taken back to my time at another institution, where I promised to view and treat the student musicians as an available pool of talent, programming variously, and incorporating chamber music. I did just that, and while one faculty member reportedly recognized and appreciated that, others forgot the idea, misunderstood the needs and benefits, and did not honor the effort. Things moved in that direction administratively here, but I did not let the lack of understanding affect the actual musical work with the players.

For the opening of this final program, I used a personal transcription for specific musicians. I poured a substantial amount of myself into creating, assigning parts for, and rehearsing that opening work. I even almost memorized the John Donne poem that the choral original had used as its text: Holy Sonnet No. 7, “At the Round Earth’s Imagined Corners.” This piece required special (paid) permission to produce, and I’m grateful to the College and the rights administrator for their support.

The major works for large orchestra and string orchestra were by Benjamin Britten, Malcolm Arnold, and Gustav Holst:

Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra (Britten)

I wanted to involve my son in a special way, so I had him do the narration. He did well, in part because he can read music and know his cues. While the opening theme and some sections were enjoyable and rewarding, I would not program this piece again. The rental cost was exorbitant. Moreover, the music is unduly difficult to put together in spots, and the parts did not entirely match the score.

English Dances, Set 1 (Arnold)

I absolutely love this music and would do it again in a heartbeat. It’s also a rental piece, and almost as expensive as the Britten above, but this was so much better scored for an average orchestra. The sonorities, the variety among the movements, the overall exhilaration . . . simply a great work.

Selections from Simple Symphony (Britten)

It was the 2nd time I’d performed this work. It is misnamed: parts are not “simple” at all!

“Jupiter” from The Planets (Holst)

Having programmed this work 19 years ago, I enjoyed coming full circle and working on it again, with an improved, more richly talented orchestra. Also, I was able to involve my talented son on his principal instrument, the euphonium, which is almost never used in orchestral music. He practiced, played the part with an older high school friend, and did very well1! A portion of the part I prepared for the now-more-common bass clef euphonium (Holst scored the the similar “tenor tuba) is shown below.

I also programmed 007 Through the Years, a medley of pop/rock tunes arranged from James Bond movies. That was mostly well arranged, but it was a bit too extended and had a bad ending, so we made some cuts and adjustments. I’ve always prided myself in the ability to make things work in a given setting—whether by writing out a part for another instrument when no player exists for the original, cutting some repeats, altering an ending, etc.

For the present, I’ve boxed up my orchestral CDs, as I won’t be needing them as resources or for inspiration.

The Musicians

I often looked out and surveyed the heads and instruments above the music stands. The age range was from 16 – 84 or so, with about 70% college students. A few were in their 60s, and one in his 80s, but most adults were younger. I count several of them as friends. As I thought about my life struggles, I would sometimes stand in amazement that these adults were willing to drive up to 30 or 45 miles one way each week just to get to play good music with others. Every single adult was supportive and encouraging. Some did service beyond the norm, and that sometimes included sympathizing.

Some of the college students received scholarship money to play, and that is normal. I suppose not every student was always motivated, and certainly not all of them practiced as much as the adults (they didn’t even have practice space available, and that situation got worse, not better, in the last couple of years), but their eyes and words and efforts remain in my heart in a good way. I think of HS and CS who returned when they were no longer students, because they liked my ensemble and our music. I think of IC and RH, male violinists who not only played exceptionally well but also led and maintained lots of good energy and good humor. I think of the responsiveness and fine musicianship of EM, OW, and EW in percussion; of AG, LB, VJ, NW, and AA in the viola and cello sections. There was PB who let out a spontaneous “breath prayer” to the Lord when faced with a difficult passage. There was AJ who was always sweet, always capable, always engaged, asking the right questions and making apt comments. And many more.

From time to time I would be asked to write recommendation letters for the students. Once or twice, it was for something I did not prefer that the person be involved in, for spiritual reasons. But the majority were absolute pleasures. In terms of ability, these students were perhaps the third best of my career so far, but in terms of average attitude, they were probably tied for the best.

Percussion had previously been more or less a bust here, until this semester: not only did four capable students almost entirely staff the percussion section, but they worked together well, cared about the sounds they were making, and grew musically over time. In other semesters, good student/shared leadership has been observed in a couple of woodwind sections. The horn section has been growing for the last two years, and it was finally a joy to hear and work with solid horns. This spring, a friendship seemed to blossom even more between a stalwart orchestra adult orchestra member and a highly talented senior student. Two new music faculty colleagues joined in for this concert. They both substantially bolstered their respective sections.

Strings in general

The strings, I have long said, are the “soul of the orchestra.” Although the woodwinds have many of the delicate solo lines in traditional literature, everything is built around the strings. Strings play in sections: all the first violins play the same part; all the seconds, etc., whereas each individual flute, bassoon, or horn player has his own part. Frankly, I don’t like the sound of strings as much as wind instruments, generally speaking. A cello or viola can be beautiful, and the double bass is foundational, but the violin is below 10th on my list of instruments. I almost never listen to a solo violin intentionally.

My ear is quickly dissatisfied in hearing mediocre string sounds, and they were in fact often mediocre. These players improved over time, of course, but there were many times that I had to ignore how bad it sounded for a while. Our orchestra averaged about 20 violins and topped out at 24 one year, as I recall. They were all students, which was a good thing, but not all of the seconds could really play.

The pairing of string players is an important factor, and I felt I was about B- at allocating players to parts and stands. In the last two years, I enlisted the help of the principal players, and I’m glad I did. They sometimes knew better than I whether a player was ripe for moving from 2nd violin to 1st violin, and who was showing leadership potential or needed mentoring. The “inside” player, positioned on the far side of the audience, is responsible for page turning where necessary, and the chemistry of players can be an important factor. Too, the players who sit toward the back can easily be neglected, so I tried on occasion to pay the right kind of attention to players in the back and middle of each section.

A more adequate rehearsal schedule in this setting would have the strings rehearsing in sectional for an hour a week and with the full ensemble for up to 4 hours per week. This change is unlikely.

Conducting and Podium Leadership

I feel some guilt on at least one front: I could have done more score study. I fancy myself a score-oriented music-maker, just as I confess being a text-oriented Christian believer. Both sets of texts are bedrock. Interpretation starts with digging into a musical (or scriptural) text to see what resides there. The original intent of the composer might be elusive at times, but we have no hope of uncovering much of it if we don’t start with the score.

I’m blessed by relatively strong score-reading ability, as well as the ability to hear in the moment, so I doubt it was apparent to many when I wasn’t as well prepared as possible. There were times my conscience accused me rightly, but I did always have something to offer, in order to help the ensemble progress each week. This kind of progress requires planning, execution of a rehearsal plan, and the ability to adjust in the moment, based on the sounds being produced. I will miss the scores, and the marks I would make. Even the post-it notes I’d often use to flag spots for rehearsal!

I’m blessed by relatively strong score-reading ability, as well as the ability to hear in the moment, so I doubt it was apparent to many when I wasn’t as well prepared as possible. There were times my conscience accused me rightly, but I did always have something to offer, in order to help the ensemble progress each week. This kind of progress requires planning, execution of a rehearsal plan, and the ability to adjust in the moment, based on the sounds being produced. I will miss the scores, and the marks I would make. Even the post-it notes I’d often use to flag spots for rehearsal!

I also have a strength with rhythm, which can be a curse (sort of like absolute [a/k/a perfect] pitch is no blessing in ensemble-music making). It can be relationally difficult when a player with strong technical ability is performing a rhythm inaccurately, but I take care with things like that. I feel pretty good about how I approach being a note/rhythm “policeman” who makes routine arrests. Typically, I will use a player’s name when complimenting him or her, but only rarely would I do that when making a correction.

At the concert, I was disappointed in a couple of the tempos I set. 3-4 clicks per minute faster would have been more exciting, but conservative tempos were OK for most of the players.

Periodically, I would make audio or video recordings of rehearsals and performances. I would always learn from these recordings! For years now, I have pined for the days when I had grad students to run video and make sure I had recordings of myself when I wanted them. Even bad recordings from a sub-optimum angle without proper mic placement would net some positive results.

It’s not just because I’m a musician whose primary training and credentials lie in conducting that I am naturally predisposed to believe in the role of the conductor. I’ve seen enough to know that good conducting makes a difference! There was a time that I overestimated my abilities to evoke sound through gesture, but I’m still generally pleasantly surprised when I see myself on video. While I am overdone at times (less is more, at least with a well-trained ensemble), I seem to feel inside myself that I’m not doing as well as I am actually doing visually. That said, I wish I’d refined certain gestures more, connected and followed through with individual melodic lines, and been a bit more confined in terms of the horizontal and vertical planes. I believe in the minimization of spoken direction, the visual evocation of sound through gesture and other nonverbals, and overall, in the wonder-filled enterprise of the instrumental ensemble!

Much more ground could be traveled, experiences recalled, and words written . . . but it is time now to close the Closure! God, give me more opportunities to lead and inspire musically.